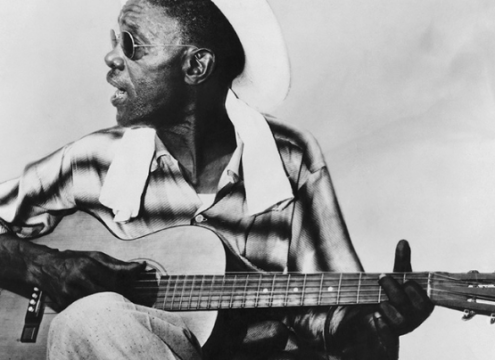

Lightnin’ Hopkins

Sam (Lightnin’) Hopkins (March 15, 1912 – January 30, 1982) was a blues singer and guitarist, born in Centerville, Texas. Though some sources give his year of birth as 1912, his Social Security application listed the year as 1911. He was the son of Abe and Frances (Sims) Hopkins. After his father died in 1915, the family (Sam, his mother, and five brothers and sisters) moved to Leona. At age eight he made his first instrument, a cigar-box guitar with chicken-wire strings. By ten he was playing music with his cousin, Texas Alexander, and Blind Lemon Jefferson, who encouraged him to continue. Hopkins also played with his brothers, blues musicians John Henry and Joel.

By the mid-1920s Sam had started jumping trains, shooting dice, and playing the blues anywhere he could. Apparently he married Elamer Lacey sometime in the 1920s, and they had several children, but by the mid-1930s Lacey, frustrated by his wandering lifestyle, took the children and left Hopkins. He served time at the Houston County Prison Farm in the mid-1930s, and after his release he returned to the blues-club circuit. In 1946 he had his big break and first studio session—in Los Angeles for Aladdin Recordings. On the record was a piano player named Wilson (Thunder) Smith; by chance he combined well with Sam to give him his nickname, Lightnin’. The album has been described as “downbeat solo blues” characteristic of Hopkins’s style. Aladdin was so impressed with Hopkins that the company invited him back for a second session in 1947. He eventually made forty-three recordings for the label.

Over his career Hopkins recorded for nearly twenty different labels, including Gold Star Records in Houston. On occasion he would record for one label while under contract to another. In 1950 he settled in Houston, but he continued to tour the country periodically. Though he recorded prolifically between 1946 and 1954, his records for the most part were not big outside the Black community. It was not until 1959, when Hopkins began working with legendary producer Sam Charters, that his music began to reach a mainstream White audience. Hopkins switched to an acoustic guitar and became a hit in the folk-blues revival of the 1960s.

During the early 1960s he played at Carnegie Hall with Pete Seeger and Joan Baez and in 1964 toured with the American Folk Blues Festival. By the end of the decade he was opening for such rock bands as the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane. During a tour of Europe in the 1970s, he played for Queen Elizabeth II at a command performance. Hopkins also performed at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. In 1972 he worked on the soundtrack to the film Sounder. He was also the subject of a documentary, The Blues According to Lightnin’ Hopkins, which won the prize at the Chicago Film Festival for outstanding documentary in 1970.

Some of his biggest hits included “Short Haired Women / Big Mama Jump!” (1947); “Shotgun Blues,” which went to Number 5 on the Billboard charts in 1950; and “Penitentiary Blues” (1959). His albums included The Complete Prestige /Bluesville Recordings, The Complete Aladdin Recordings, and the Gold Star Sessions (two volumes). Hopkins recorded a total of more than eighty-five albums and toured around the world. But after a 1970 car crash, many of the concerts he performed were on his front porch or at a bar near his house. He had a knack for writing songs impromptu, and frequently wove legends around a core of truth. His often autobiographical songs made him a spokesman for the southern Black community that had no voice in the White mainstream until blues attained a broader popularity through White singers like Elvis Presley. In 1980 Lightnin’ Hopkins was inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame.

Hopkins died of cancer of the esophagus on January 30, 1982, in Houston. He was survived by his caretaker, Antoinette Charles, and four children. His funeral was attended by more than 4,000, including fans and musicians. He was buried in Forest Park Cemetery in Houston. In 2002 the town of Crockett in Houston County, east of the birthplace of Hopkins, erected a memorial statue honoring the bluesman in Lightnin’ Hopkins Park. He is also honored in the Houston Institute for Culture’s Texas Music Hall of Fame. In the 2010s a documentary, Where Lightnin’ Strikes, was in production.