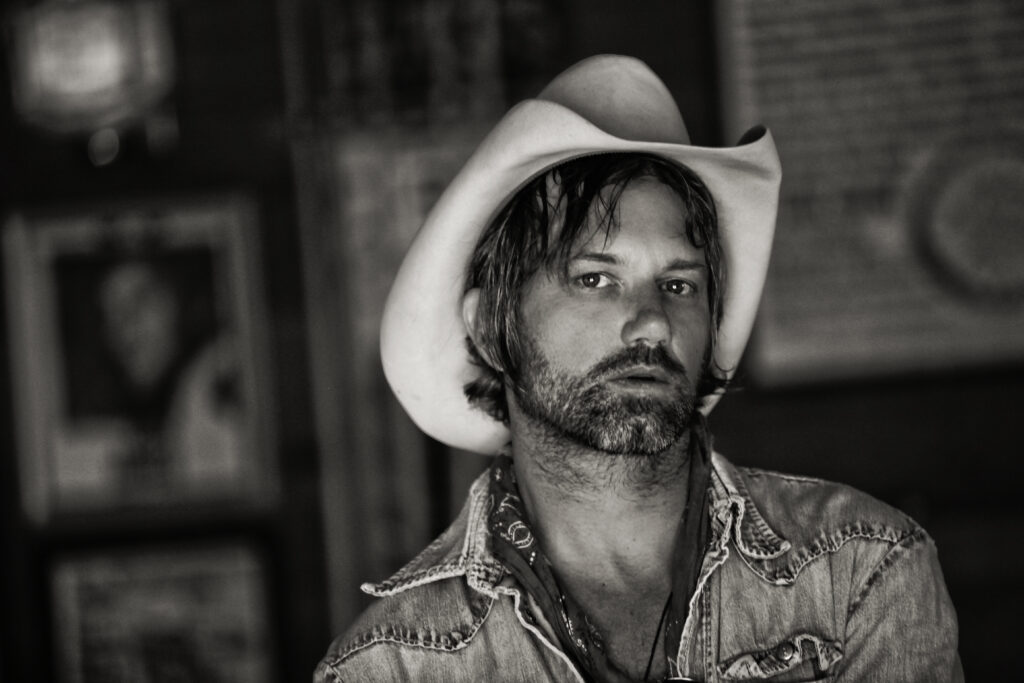

Keith Gattis

Keith Gattis left Texas to become a star. Instead, he became great.

Gattis is a favorite songwriter of legends and a patron saint of telecaster disciples. His voice––distinct, smooth, and sad––made believers out of cynics and mined classics out of shadows.

“To me, Tom Petty was a country singer and Johnny Cash was a rock star,” Gattis liked to say. The observation is signature Gattis: direct, contrarian, and perceptive. And while he revered and studied pillars of honky tonk and West Coast rock-and-roll, Gattis became a force by leaning wholly––stubbornly––into being nobody but himself.

Gattis wrote about pain and belief with unnerving tenderness. His “El Cerrito Place,” recorded by Charlie Robison, Gattis himself, and later, Kenny Chesney, became a standard. Rolling Stone called the song “a masterclass in conveying longing and regret,” while journalist Chet Flippo wrote, “Just listen to it sung. It will hypnotize you.”

The roots of Gattis’ earnest independence begin in Central Texas, where he grew up participating in Future Farmers of America (FFA) and riding bulls. He started his first band at 17. In 1992, Gattis moved to Nashville from Texas with $800 in his pocket. His first steady gig? Touring as a guitarist with Johnny Paycheck.

Gattis inked record deals with RCA twice. RCA Nashville released Gattis’ eponymous debut in 1996, but that initial partnership ended soon amidst country radio’s protests that Gattis was “too country.” He’d go on to spend his life writing and recording, but the limited amount of solo work he released––just two albums, about a decade apart––can be traced directly to a frustrating music business trope: Industry machinations and executive shuffles kept getting in art’s way.

While Gattis’ first album was a brilliant interpretation of the classic country sounds that had shaped his early life, the music he felt compelled to make was evolving. Nashville started to feel too small.

In 2001, Gattis moved to Los Angeles. He found an inclusive West Coast country music scene that embraced his raw blend of alt-rock and honky tonk. Gattis’ love of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, The Wallflowers, and other blues and folk-inspired giants began in the South, but in California, Gattis felt free to push further into his own roots rock that remained unashamed of its twang.

Living at El Cerrito Place in Hollywood was a transformative experience for Gattis. There, he wrote and recorded what would become his critically acclaimed Big City Blues album. He connected with musicians he’d long admired, including Rami Jaffee and Waddy Wachtel, both of whom contributed their talents to the record. Released in 2005, Big City Blues is a feat of storytelling and musicianship that cemented Gattis’ place in American music.

Gattis didn’t just liberate himself in Hollywood. He bet on other artists, too. Gattis recognized a fellow traveler in Waylon Payne, whose pining rock-and-roll country was too rich and layered for executives wary of risks. Gattis knew what he heard––and in addition to producing and playing guitar on Payne’s record, he took out the loans to get it made himself. Entitled The Drifter, Payne’s 2003 album led to a major label deal with Universal, and ultimately became an underground roots music masterpiece.

Together, Payne and Gattis had also begun playing to packed LA rooms. Along with other aces including Travis Howard, they launched Eastbound and Down, a local residency featuring 1970’s honky tonk covers. Soon, familiar faces like Dwight Yoakam joined the crowds. Yoakam loved what he saw and offered Gattis a job.

Gattis served as band leader and co-producer for Yoakam, and Gattis’ guitar playing became a trademark. He mastered the telecaster. Then, Gattis reimagined what B-Bender Teles could do, and ultimately began making his own versions of the instrument including the B-Bender he built to play on Yoakam’s celebrated 2005 album Blame the Vain.

Inspired and ready to tour playing his own songs, Gattis packed up and left LA for Austin after releasing Big City Blues that year. Nashville noticed. After signing a new deal with RCA, Gattis moved back to Music City––and recorded a new album that the label never released.

Determined to maintain his hard-won voice, Gattis kept making music––and other artists kept returning to Gattis’ well. Gattis’ songs have been recorded by Kenny Chesney, George Strait, George Jones, Willie Nelson, Gary Allan, and many more. Today, artists still turn to Gattis, not just for inspiration, but for new material. A case in point: In 2024, Koe Wetzel recorded “Reconsider,” a track from Big City Blues.

Once Strait discovered Gattis, he stuck with him, recording many Gattis songs across multiple records. Gattis wrote three songs on Strait’s 2024 studio album including the title track “Cowboys and Dreamers” and “Rent,” co-written with Guy Clark. Before launching into “Rent” on the album, Strait recorded a spoken tribute: “This song was written by Keith Gattis, an amazing songwriter, singer, and guitar slinger,” Strait says. “We lost Keith way too soon.”

Restlessly creative, Gattis launched Pioneertown Recording Studio in East Nashville in 2012. He deepened his role as a trusted guide and collaborator of fellow independent thinkers, producing albums for Kendall Marvel, Wade Bowen, Randy Houser, Mickey and the Motorcars, and others.

At Pioneertown, Gattis also worked on High Desert Low. Produced by Gattis, the album features him playing and singing his own songs––and has earned a heady reputation: Those lucky enough to have heard the unreleased record point to it as a career highlight. High Desert Low captures Gattis at the height of his power, wrestling through track after track of soulful vocals, poignant writing, and ferocious guitar. Plans are underway to release the recording.

In April of 2023, Gattis died after a tragic tractor accident at his home. The loss devastated his young family, friends, and musical peers who had come to rely on his vision, as well as the devoted grassroots following who had long-since recognized his subtle genius.

In the end, Gattis left everyone who knew him and his songs wanting more. He also did exactly what he set out to do.

“I got lucky and had a little success,” Gattis said. “It got me enough money to pay off my debts, get square with the tax man, and put a down payment on my house. There were a lot of good reasons to give up. It’s butt kicking to say the least. I thought I was going to be a star, but I never really wanted that. I wanted a great career so I could play music for the rest of my life, and that’s what I’ve ended up with. And if I need to blow off steam, I’ll just go play the Family Wash.”